What if the real story of strategy isn’t in what’s measured—but what’s hiding between the lines? We dive into data to reveal how competition drives strategy.

A few weeks ago, after hosting a webinar on the data in our 2026 Strategy Planning Report, I got an email that stuck with me.

The session had been well-attended—we walked through data from over 20,000 strategic plans, 100,000 objectives, and 200,000 measures tracked in ClearPoint. It was a lot of information to digest. But one viewer, a strategist working on a book, had zeroed in on a simple, brilliant question:

"How many organizations have a strategic initiative focused on strengthening their competitive advantage?"

I read the question twice.

I’ve spent the better part of two decades helping organizations measure and manage strategy—first as a consultant, then co-founding ClearPoint, and along the way working closely with people like Bob Kaplan and David Norton. But this question—despite how central it seemed—wasn’t one I had ever tried to answer directly.

We help our clients build scorecards, track measures, report on initiatives... but how often do we look across them all and ask: "Where is competition explicitly showing up?"

So I did what I usually do when something sticks: I got curious. I called in the team. And we started digging.

Haven’t seen the 2026 Strategy Planning Report yet? Get your free copy—filled with insightful data on strategic performance—here!

First, The Numbers

We ran a search using two lenses.

The first was what I’d call a "business school lens" — we looked for terms straight out of a strategic management textbook:

- "competitive advantage"

- "market leader"

- "benchmarking"

- “outperform"

- “rival"

These are phrases I remember debating back when I was learning from Kaplan and Norton. They’re sharp, clear, and loaded with intent.

Result? Out of 52,131 initiatives, only 219 matched. That’s 0.42%.

That felt... small. Too small.

So we expanded the search. We asked: What if organizations are thinking competitively, but just not using textbook terms?

We built a broader query to include industry-specific performance metrics:

- Annual recurring revenue (ARR) growth for SaaS

- Average daily rate (ADR) for hospitality

- On-time performance for airlines

We also looked at economic development, business attraction, platform building, ecosystem growth—terms that function as competitive proxies.

Now the number jumped to 1,306 initiatives. That’s 2.51% of the dataset.

Better. But still surprisingly low.

The Language of Strategy Is Changing

What hit me in this analysis was just how rarely organizations talk directly about competition. And yet they’re clearly acting on it.

Over the years, I’ve worked with banks that talk about wallet share, universities trying to climb national rankings, cities developing business parks to lure companies away from their neighbors.

But rarely do they use the word "compete."

Why? Because the language of strategy has evolved.

In my early days, I saw plenty of plans with bold headlines: "Achieve #1 Market Position" or "Outperform Rivals Through Differentiation." That kind of language was especially common in for-profit, high-competition sectors—financial services, consulting, tech.

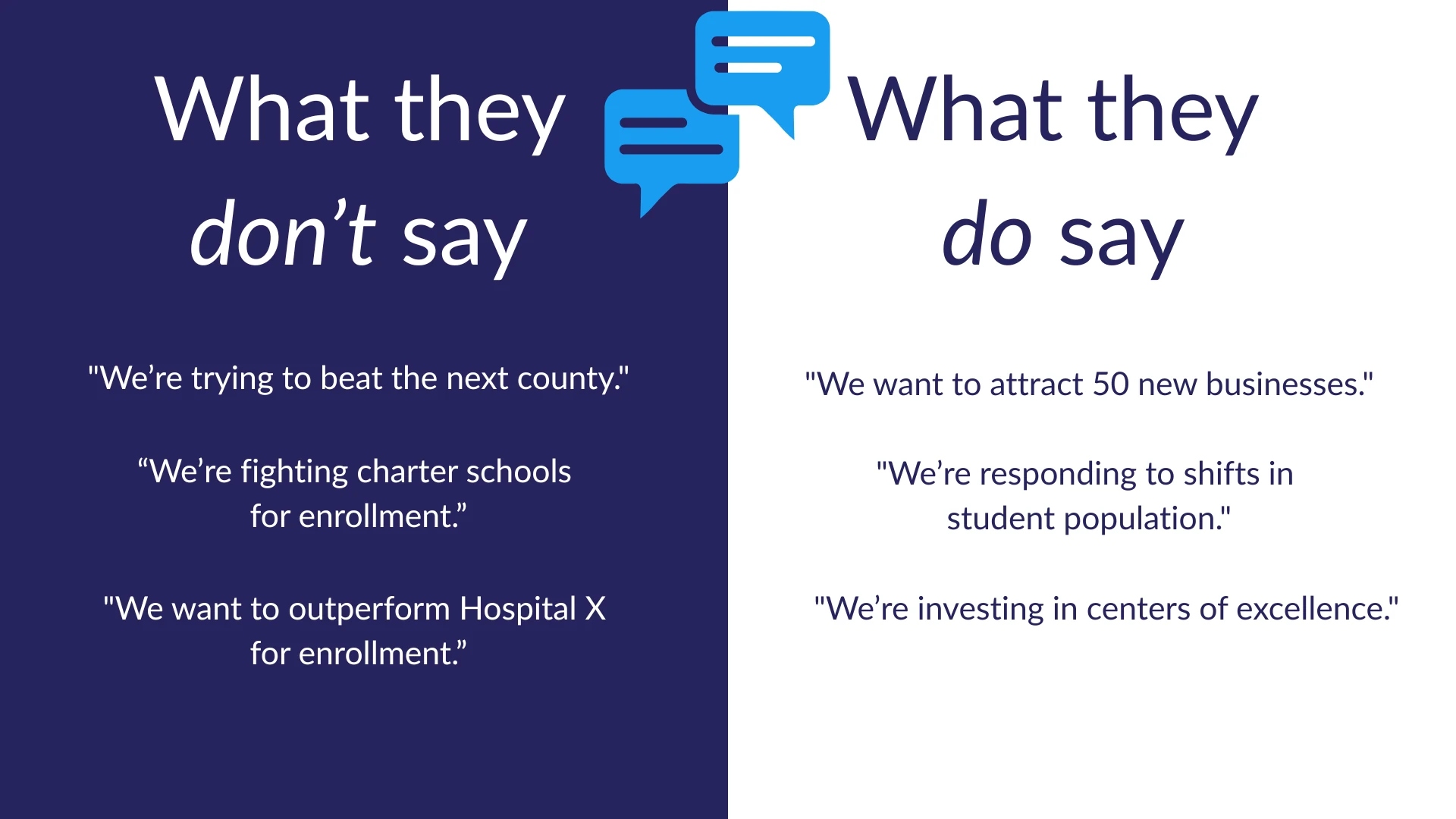

But then I started working more with government agencies, school districts, healthcare providers. These organizations compete just as fiercely—for talent, for funding, for outcomes—but they use different language.

<blockquote><p>A city doesn’t say:<em> "We’re trying to beat the next county."</em><br />They say, <em>"We want to attract 50 new businesses."</em></p></blockquote>

<blockquote><p>A school district doesn’t write, <em>"We’re fighting charter schools for enrollment."</em><br />They say,<em> "We’re responding to shifts in student population."</em></p></blockquote>

Same strategic intent. Different tone.

Strategy's Dark Matter

This realization reminded me of something I once heard Francis Gouillart say about strategy: "What you can’t see often matters more than what you can."

That’s exactly what this data is showing us. There’s a kind of dark matter in strategic planning—invisible forces shaping decisions, direction, and resource allocation. Competition is one of those forces.

Just because it’s not labeled doesn’t mean it’s not there. It’s there in the way a hospital expands its cardiology service line. In how a transit authority aims for 90% on-time performance. In a SaaS firm pushing for 40% ARR growth.

None of those use the word "compete." But they're clearly strategic moves made with rivals in mind.

Real-World Examples from the Data

The deeper we went, the more fascinating the patterns became.

- Government was one of the most competitive sectors in our dataset—just not explicitly. Cities and counties were constantly trying to attract residents, businesses, and federal grants. But out of 233 government initiatives we flagged as competitive, only one used traditional competitive language. The rest spoke in terms of "economic development" or "placemaking."

- Technology companies focused heavily on ARR and ecosystem development. You could see clear platform strategies unfolding—ways to build moats and create network effects—but no one said "barriers to entry" or "market dominance."

- Healthcare organizations were investing in "centers of excellence" and specific service lines, positioning themselves to draw patients from wider regions. Again, no one said "we want to outperform Hospital X," but the competitive undertone was unmistakable.

These examples are what convinced me that the 2.51% figure undercounts real competitive activity. A more realistic estimate?

I’d say 10-20% of strategic initiatives are truly competitive—but just not labeled that way.

Why This Matters for Strategy Leaders

So what do we take from this?

If you're a strategy leader, a chief of staff, a performance manager, this analysis should give you pause.

Because if your organization only recognizes competition when it’s spelled out in the plan, you're missing the big picture. You might already be competing in important ways—you just haven’t called it that.

I’ve sat in meetings where teams struggled to frame their work in strategic terms. They’d say, "We’re just trying to improve operations." But when we looked closer, they were benchmarking, investing in service delivery improvements, or launching new services that clearly differentiated them.

That is strategy. That is competitive thinking.

Sometimes all it takes is shifting the frame.

One Question, Many Possibilities

Here’s what excites me most: This all started with one question from a curious webinar attendee! One good question turned into a multi-layered exploration of how organizations think and talk about strategy.

And it made me realize: If that question was hiding in our data, how many others are waiting to be asked?

What if we explored:

- How strategic priorities shift after a CEO change?

- Whether innovation initiatives cluster in certain industries or market conditions?

- What performance metrics signal emerging trends across sectors?

With a dataset this large—200,000 measures, thousands of plans—we can start asking big-picture questions that help us understand not just one organization, but the collective behavior of hundreds.

It’s a strategy researcher’s dream.

An Invitation To Get Curious

We didn’t launch ClearPoint just to build dashboards. We wanted to help people make better strategic decisions. This analysis reminded me why that matters.

So if you’re working on strategy—at any level—I want to encourage you to get curious. Don’t just track your measures. Interrogate them. Ask what they’re really telling you.

Ask what your competitors might be doing that you’re already responding to.

And more than anything: Don’t underestimate the power of a single, thoughtful question.

This one changed how I look at 200,000 measures. What will the next one do?

.svg)

![Why Strategic Planning Fails (And What To Do About It) [DATA]](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/637e14518f6e3b2a5c392294/69792f326ab0b1ac3cc24675_why-strategic-planning-fails-and-what-to-do-about-it-data-blog-header.webp)